Posts Tagged ‘dental’

#Inclusion

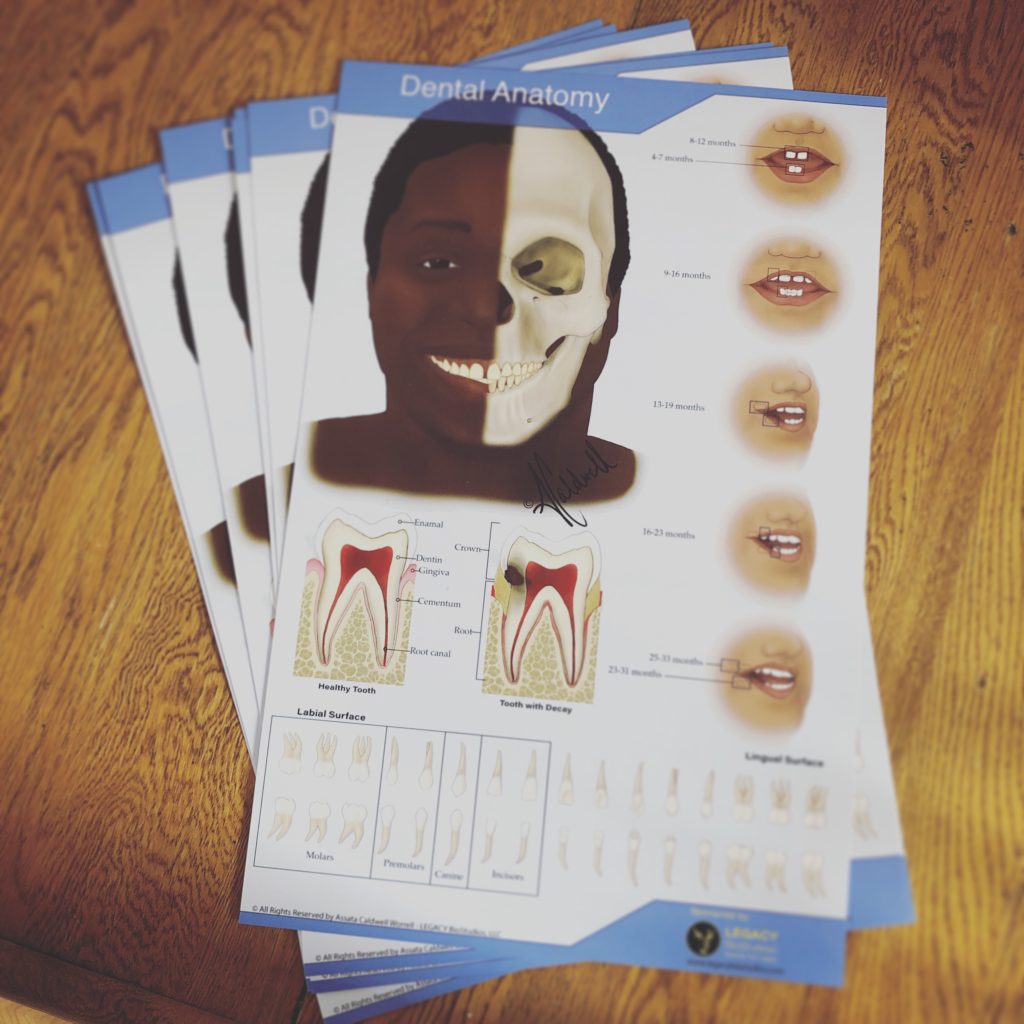

Why Diversity and Inclusivity Matters in Medical Illustration I was in the 2nd grade, and a friend told me my gums were dirty. My mom is a dentist and was asked to come to my 2nd-grade class to do a lesson on oral hygiene and the importance of preventative health care. Mostly a “don’t be…

Read More