The Unique Case of Sinistra

In early December of 2019, Dr. Maurine Neiman invited me to the Neiman Lab at the University of Iowa, where I had the honor of observing a remarkable once in a lifetime mutation of the Potamopyrgus antipodarum, a species of freshwater snail native to New Zealand.

Upon reaching the lab, Dr. Neiman told me that they had found a one in a million find and wanted to have it illustrated and archived. They didn’t feel comfortable putting this snail asleep to get photographs because the anesthesia could kill her. The discovery was a female snail which they named Sinistra due to her left-oriented shell (https://uiowa.edu/stories/marissa-roseman-research-discovery). Sinistra had a genetic twin, Dextra, whom I was able to use to compare Sinistra. Dextra would be my control, and I will identify her in this blog as the “standard” morphology of Potamopygrus antipodarum. My original goal was to compare and contrast Sinistra’s and Dextra’s morphologies.

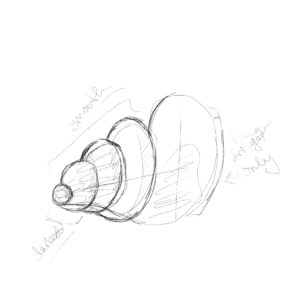

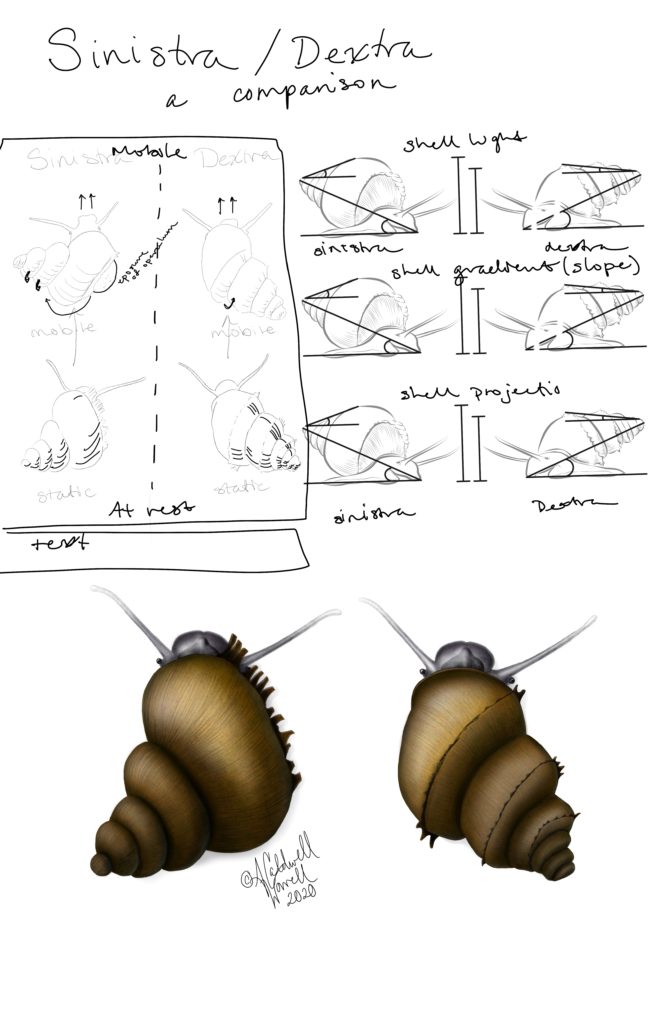

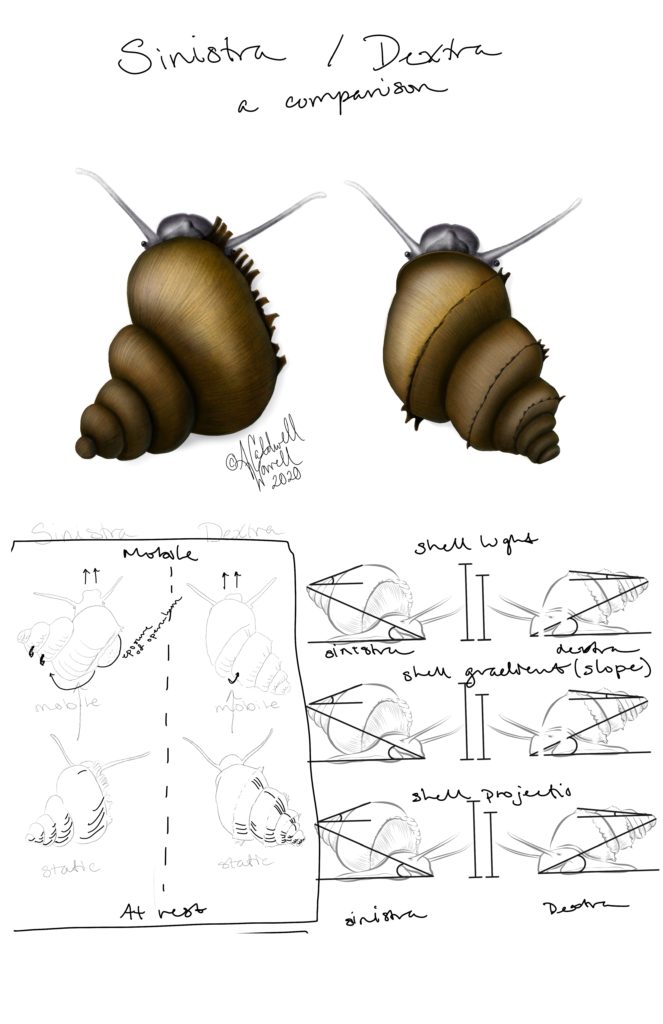

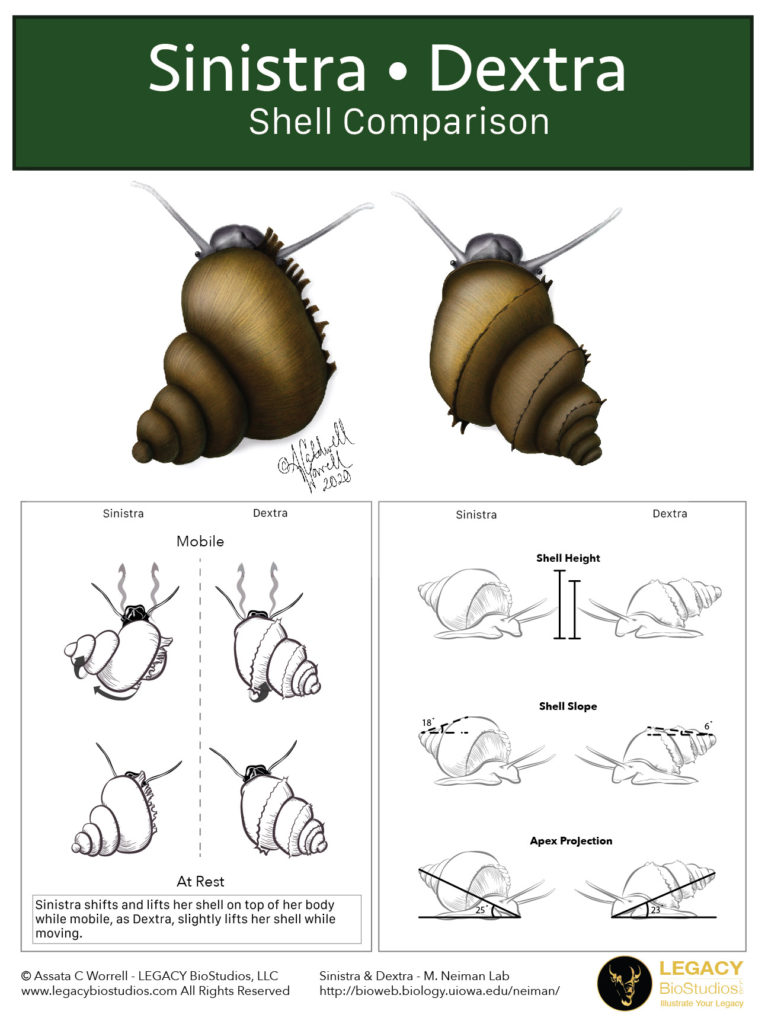

Upon initial observation, Sinistra had a whorl projection to the left rather than to the right, which is the standard projection of a whorl. Sinistra also had a curvier roundness to her shell body and a kind of fringe towards the mantle’s edge, while Dextra’s shell was more angular, and had a ridge along the shell body and whorl.

While watching Sinistra, I also noticed her movements and observed that Sinistra’s mobility seemed to be awkward and hindered. Most snails move rather smoothly by contracting their foot muscle, and this allows very smooth movement forward. Sinistra seemed to struggle and had to wiggle around a lot to be able to move forward.

My hypothesis was Sinistra’s mobility issue was due to her shell. Sinistra’s shell seemed to be cumbersome to her, and this was particularly evident when Sinistra was placed on her back and struggled to flip back over as quickly as her counterpart Dextra.

After several hours of observation, I created a shell comparison of Sinistra and Dextra focused on the color, shape, and form of their shells.

I was given access to an archive of photographs and videos of Sinistra and Dextra for repetitive and slower viewing. I first watched footage of Sinistra walking on repeat in slow motion. While scrubbing through the footage, I was able to see Sinistra turn and lift her shell on top of her body before starting to move and kept it raised during her spurts of movement.

If the reduced mobility was genuinely due to the shell, I needed to get a numerical comparison for Sinistra’s and Dextra’s shells!

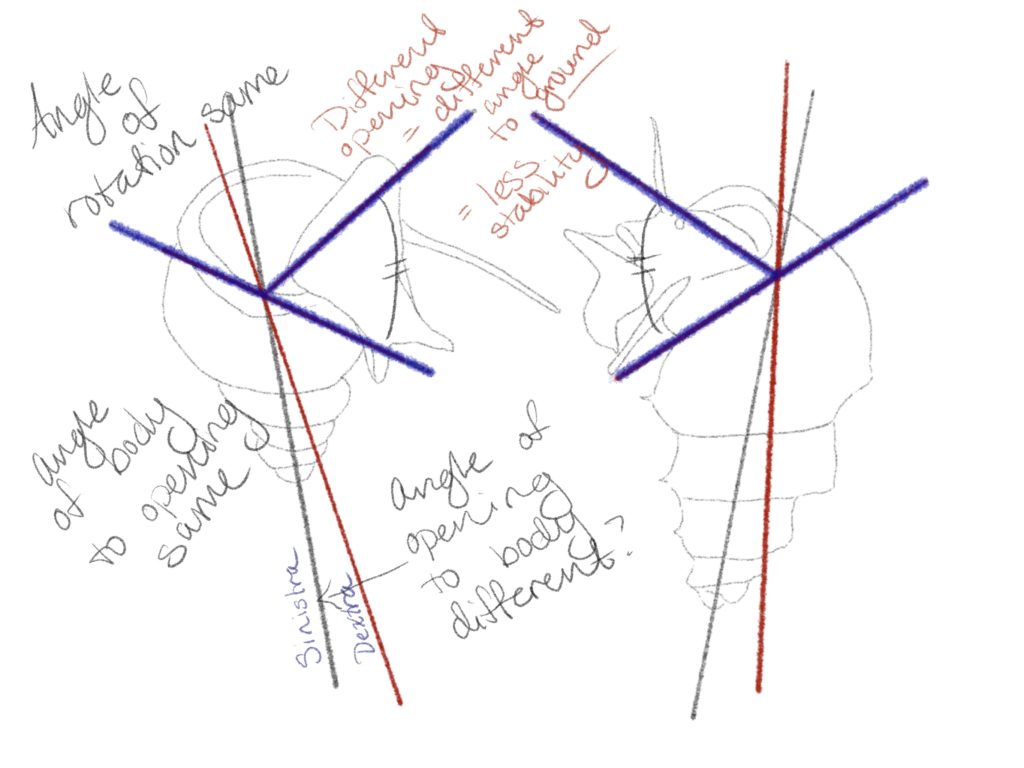

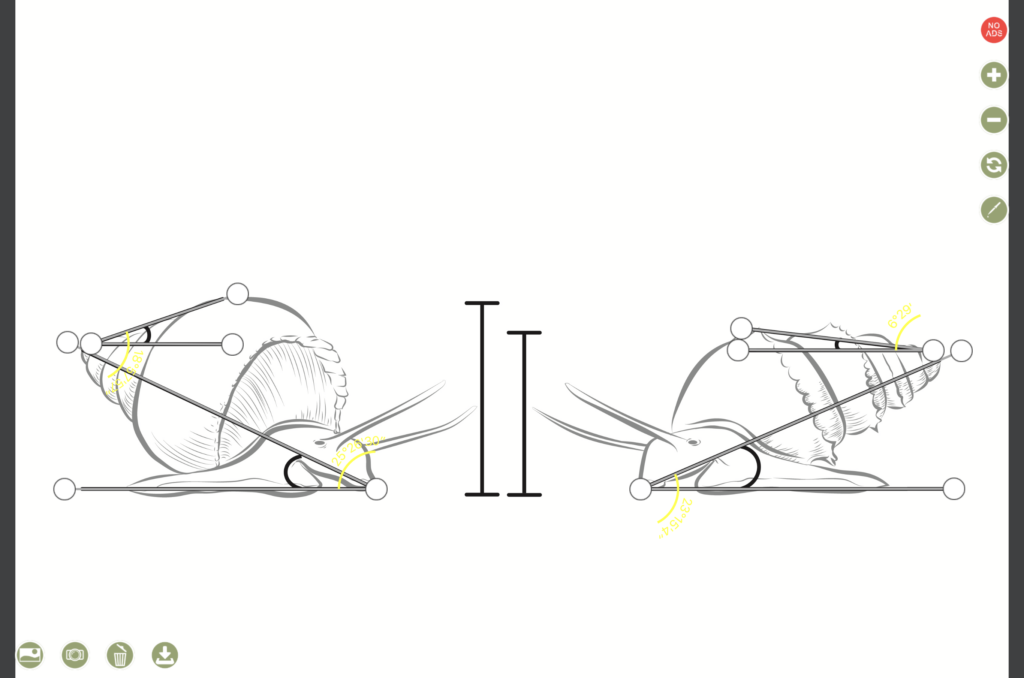

I used archived footage to see both snails profile views, which I measured and sketched. From those sketches, I compared the snails’ height, shell slope, and apex projection.

The difference in shell height was obvious.

To measure angles, I downloaded the app AngleMeter.

In the app, I was able to download my illustrations and place the digital compass on the slope measuring the most top point of the apex. To measure the apex projection, I used the tip of the nose for the anchor point and had the projection mark on the very tip of the whorl.

I observed:

Sinistra had a taller height than Dextra

Sinistra’s slope was more severe at 18 degrees, as Dextra’s slope was 6 degrees.

Sinistra’s apex projection was more severe than Dextra’s as 25 degrees, while Dextra’s was 23 degrees.

These measurements prove that Sinistra’s shell was significantly different than Dextra’s and certainly made flipping over from her back more difficult.

The hight and angles put Sinistra higher up from the ground and made it harder for her to reach and find enough balance to flip back over. Due to the largeness to her shell and odd angles, I suspect simply for comfort, Sinistra lifted her shell to allow a little more freedom to move.

Sinistra was a remarkable find, and her existence shows another example of the impact of genetics and their mutations.

Why a poster?

Initially, we wanted to archive Sinistra’s existence, but our scope had grown. Dr. Neiman and I decided a poster would be an effective way to show what I had deduced regarding Sinistra’s mobility and provide the lab with something special to commemorate such a find!

A poster tells a story. What was our story?

My collaboration with the Neiman lab was almost purely visual. My notes were mainly sketches, and my research was done in person and with video footage provided by the lab. We wanted our communication to reflect that.

A poster would tell the story!

My story timeline:

– Comparison

– Mobility

– Hypothesis

– Research Results

The poster needed to reflect my timeline in some way, so I started sketching out the poster format with my timeline of discovery in mind.

The first one showed my timeline in reverse, displaying the mobility and research first, but I didn’t like the line drawings on top. I actively wanted to use the poster to display Sinistra.

The final poster was 18″x24″, laminated, and is now affixed to a wall in the Neiman Lab.

I was 22 the last time I worked in a lab. It was particularly nostalgic and rewarding to collaborate in such a way to contribute to Sinistra’s research. Sinistra has since passed, so knowing I helped visually record her moment in time has been a unique and humbling experience within itself.

Click here for more information on the Neiman Lab and Sinistra.

Be sure to follow Dr. Neiman on twitter @mneiman for more snail updates!